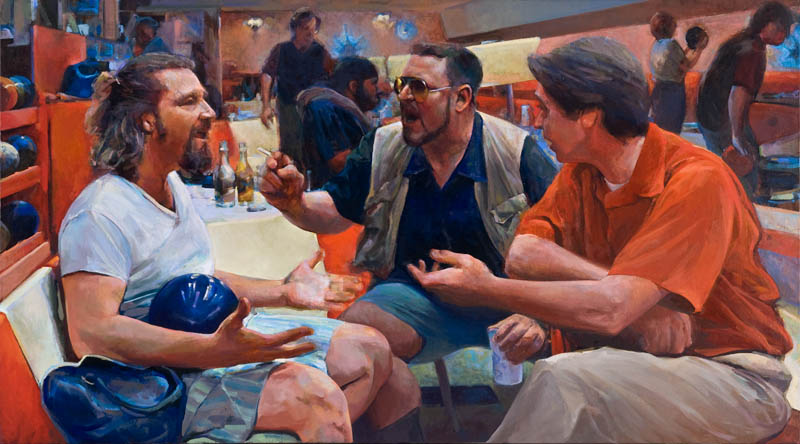

(“Oath of the Horatii” painting courtesy of the artist, Joe Forkan)

For about ten years now, I have watched The Big Lebowski on my birthday. If you have seen the film, you will easily remember one of its first scenes: two thugs have erroneously broken into The Dude’s apartment to shake him down, having mistaken the disheveled “loser” for a millionaire who has the same name, Jeffrey Lebowski. As one of the thugs, Woo, “micturates” on The Dude’s rug, he utters a seemingly Shakespearean line, and I realized this year that I had never before heard it properly: “Ever thus to deadbeats, Lebowski.”

The “deadbeats” part makes perfect sense: The Dude is seen by nearly everyone in the film as a layabout hippie, a non-contributor. But “ever thus?” Hardly the phrase one expects from a hired goon, particularly one whose idea of articulating his displeasure is aggressive urination. A quick investigation reveals that “Ever thus to deadbeats” is a paraphrase of “Ever thus to tyrants,” or “Sic semper tyrannis,” a pronouncement supposed to have been made by Brutus as he helped murder Julius Caesar. The phrase has subsequently been invoked by, among others, Virginia as its state motto, John Wilkes Booth as he assassinated President Lincoln, and Crazy Joe Davola, Jerry’s would-be assailant on Seinfeld.

A reference to throwing off tyranny is not at all out of place in The Big Lebowski: the film’s prologue features the first President Bush on television, taking a stand against the tyranny of Saddam Hussein (another character in the Lebowski universe), insisting, “This will not stand—this unchecked aggression against Kuwait.” The Dude’s best friend, Vietnam War veteran Walter Sobchak, looks for any opportunity to free himself from oppression—perceived or otherwise—even yelling at a grandmotherly waitress who has the nerve to ask him to keep his voice down after he shouts profanity in a quiet coffee shop. Moreover, there’s the tyranny of Woo soiling The Dude’s rug as he does the bidding of Jackie Treehorn, the terror campaign of the nihilists who smash up The Dude’s private residence, and the fascism of the Sheriff of Malibu, who lambasts The Dude both physically and verbally, “stay out of Malibu, Lebowski—stay out of Malibu, deadbeat.”

However, what is so bizarre about Woo’s Sic semper is that he attacks the tyranny of The Dude’s desire simply to be only after it is clear that they have staked out the wrong Lebowski. Throughout the film, The Dude’s commitment to absolute, peaceful being is contrasted with a zealous drive to achieve: the millionaire Lebowski boasts of his achievements in business, charity, and political connections—just think of his “Time Man of the Year” magazine cover made from a mirror! And because Mr. Lebowski has achieved in spite of a physical disability, he expects The Dude to be even more impressed with his self-serving accolades and, consequently, The Dude should be even more ashamed of his own failure to achieve. Mr. Lebowski berates The Dude’s wardrobe, intelligence, and lifestyle, insisting that his “revolution is over,” and that “The bums will always lose!” The Dude is deplored not only because he does not serve Mr. Lebowski’s vainglory, but also because he does not buy into the ideology of achievement: he isn’t even employed—the horror!

The pursuit of achievement embodied by the millionaire Lebowski is macroscopically represented by the film’s many references to America’s Manifest Destiny. To call The Big Lebowski a Western may seem peculiar, but it self identifies with this genre, one that has in the history of literature and cinema expressly promoted the Manifest Destiny agenda. Narrated by a cowboy known only as The Stranger, the film begins with a desert landscape, a tumbleweed, a song called “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” and the line “A way out West, there was this fella . . . .” With his cowboy hat and drawl, The Stranger is our link to the motifs of the old Westerns, and less-obvious tokens keep us in mind of Manifest Destiny throughout the story, such as little Larry Sellers’ social studies homework on the Louisiana Purchase and Smokey, the film’s only Native American Indian character. The mere accusation of Smokey having stepped over the line into forbidden territory while bowling is enough to send Walter, the Vietnam veteran, into a violent rage during which he points a loaded gun at Smokey’s head and forces him to change a written document under duress. By 1991, when the film takes place, the westward advance of American civilization has long since ended, and Los Angeles is as far west as our Manifest Destiny can take us. “Westward the wagons” and the pioneer work ethic have given way to laziness and decadence. And The Dude is, in the words of The Stranger, “the man for his time and place”—in this time and place, he is the hero of the Western, the somewhat absurd culmination of America’s Manifest Destiny.

While everything around him works within the paradigm of achievement, The Dude simply wants to “abide.” Understanding what it means to abide has been my way into understanding Woo’s dictum, “ever thus to deadbeats.” The word is only uttered three times in the course of the movie: first, by the millionaire Lebowski who swears to The Dude, after handing him a severed digit (ostensibly belonging to the millionaire’s wife), “By God, sir. I will not abide another toe.” The sense of “abide” here is “to tolerate, endure, or withstand.” Mr. Lebowski, who has concocted this double-cross to frame The Dude for stealing Bunny’s ransom money, insists that he will not abide any further harm to a wife he actually hopes will be murdered by her captors. He feigns exasperation and refuses to endure any further tyranny from the situation he, in fact, controls. His pseudo-achievements and his unwillingness to abide contrast directly with the most significant instance of “abide,” which comes from The Dude himself in his last proper line of the film: “The Dude abides.” The line is immediately repeated by The Stranger in a direct address to us, the viewers. “Abide” in this context has most readily been interpreted as “to live” and, more specifically, as an encapsulation of The Dude’s Zen desire to just be. While this meaning of “abide” certainly holds, I want to suggest an additional, complementary meaning: “to pay a price; or, to suffer for.”

Curiously, this is the same usage of “abide” that is found in Julius Caesar. Brutus speaks to the conspirators and witnesses, saying “let no man abide this deed, / But we the doers.” The deed is the murder of Caesar—during which, incidentally, Shakespeare does not have Brutus speak the line, “Sic semper tyrannis”—and while Brutus means something different, Caesar is the one who has literally abided and, simultaneously not abided, it. He has suffered the consequences of their deed, but he has not survived to continue abiding. Far from this explicit meaning, however, Brutus here intends that no one should suffer the consequences of Caesar’s murder but the conspirators themselves; he has convinced himself that theirs is a just crime and that they are, therefore, safe from judgment. By using the word “abide,” however, he simultaneously curses himself and his co-conspirators, commanding that none should live with this deed, nor suffer it to go unpunished, and the plebeians quickly say as much: “If it be found so [i.e. that Caesar was not ambitious] some will dear abide it.” Ultimately Mark Antony & Co. do not abide the murder, and Brutus, Cassius, et al. are made to abide their deed.

“The Dude abides.” He is neither ambitious nor tyrannical—he just wants to be. He tolerates the tyranny of those who label him a loser deadbeat bum. And, as The Stranger points out, he suffers on our behalf in an inverted Christ narrative: “The dude abides . . . I don’t know about you, but I take comfort in that. It’s good knowin’ he’s out there, The Dude, takin’ her easy for all us sinners.” In this version of the Western, the cowboy’s task is laid to rest long before the narrative begins, and he is free to drift with the tumbleweeds, ultimately unharmed by the worries of civilization, be they thugs, nihilists, slow-witted middle-schoolers, phony millionaires, pedophile bowling rivals, price-gouging morticians, or known pornographers. He can absorb and diffuse that which the world rolls his way. On a conquered frontier governed by inertia, where the tyrant is the one who proclaims Sic semper, this long-haired, bearded, sandaled peace lover, abiding our sins, is the one who has transcended the triviality by being ultimately trivial. So, when my next birthday comes, I’ll watch the movie again and abide getting another year older as best I can, knowing that a way out West, The Dude will abide the rest for me.